February 2021 - BME Blaze: Michael Sutton

In this monthly spotlight, get to know the alumni and students of Columbia's Department of Biomedical Engineering. Read what our BME folks are up to, from our labs' latest research, to our students' plans for the future, to our teams' innovations, start-ups and other career successes.

We enjoyed catching up with Columbia BME 5th year PhD candidate, Michael Sutton (M.S. '18), as he discussed his academic journey, his experience as a Columbia BME graduate student, and his advice to future BME students.

Read below to get to know Michael!

Michael Sutton

M.S. '18, Biomedical Engineering

Current 5th Year Ph.D. Candidate, Biomedical Engineering

Noteworthy Achievements

NIH Trainee, NSF Fellow, JKCF Scholar, SMDP MedTech Scholar

Where are you from?

Aliquippa, PA

What is your current position?

5th year Ph.D. student

Tell us about your research journey.

I started at Columbia in Fall 2016 in the Cell and Molecular Biomechanics Lab (CMBL) under Dr. Christopher Jacobs. Our lab studied how to use the body's natural bone remodeling process to develop more effective therapeutics for osteoporosis. The CMBL was among the first to identify the osteocyte primary cilium, a solitary antenna-like organelle, as a mechanosensitive signaling nexus that contributes to bone adaptation. My project focused on understanding the degree to which the primary cilium of macrophages regulated osteoclast differentiation and function. Dr. Jacobs passed away in July of 2018 after a long battle with cancer. Rather than navigate the larger half of my Ph.D. without the help of the expert in the field I was studying, I opted to transfer labs, joining the Microscale Biocomplexity Laboratory (MBL) and am now being advised by Dr. Lance Kam. The MBL focuses on using engineered surfaces and biomaterials to study T-cell mechanobiology. In particular, our lab previously demonstrated that the activation of T cells is affected by the mechanical response of their surroundings. My project hopes to elucidate the mechanism by which components of the cytoskeleton translocate during T-cell activation, an understanding that will hopefully lead to new immunotherapeutic targets.

How did you become interested in STEM research and, more specifically, in biomedical engineering?

I was always drawn towards math and science as a kid. When I was finishing high school, I decided I would be pre-med and thought majoring in biomedical engineering would allow me to gain exposure to the technological side of the medical field. But, while I was in college, I decided that the physician’s life would not be for me. I also realized that biomedical engineering was a pretty cool discipline in and of itself. An old professor once told me, “When our society faces a health problem, it’s biomedical engineers who often create the solution; doctors usually just prescribe it.”

Tell us about your family. Who has/have been your strongest influence(s) in life?

I grew up feeling like an only child in a single-parent household. I say “feeling,” because my dad was technically around but didn’t play an active role in raising me, and my only brother was so much older than me that we didn’t really start bonding until I was an adult. I’m the first person in my immediate family to graduate from college and will be the first in my extended family (that I’m aware of) to earn a Ph.D. My mother and grandmother have been the strongest influences in my life. I didn’t have many positive male figures growing up, so the women in my family were who I looked up to. My mother in particular has always been my biggest supporter and voice of reason, and my grandmother has acted as my spiritual guide. There’s no way I would be where I am today without the two of them.

Terminology question: Do you prefer “Black” or “African-American” or other?

Short answer: Black. Longer answer: I think it depends on the context and intent, but this is a very complex and nuanced question that necessitates some historical understanding. Portugal began the transatlantic slave trade in the 15th century, referring to a slave as “Negro,” the Portuguese word for black. “Negro” existed in some capacity in the European and American lexicon for nearly half a millennium. It wasn’t until the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s that some Black people began using “Black” as a term of power and pride (e.g., Stokely Carmichael touting the slogan and philosophy of “Black Power” in 1966, and James Brown’s Say it loud! I’m black and I’m proud in 1968). Then, in the late 1980s, led in large part by Jesse Jackson, a campaign began with the goal to establish “African-American” as the proper descriptive term, in part because as immigration to the U.S. increased throughout the 20th century, more and more people who identified as Black were likely to be first and second-generation immigrants (many from Africa, Europe, and the Caribbean) without a direct connection to American slavery. All that being said, I personally identify as Black 95% of the time, largely because I can’t trace my roots. When I think about the lingering impacts of American slavery and colonization, part of what was stolen was that lineage. I have zero cultural connection to Africa; I think I even prefer the term “Black American” over African-American. In today’s society, the latter just seems like an attempt at political correctness. Identifying as Black makes me a part of the greater African diaspora, and in America in particular, my daily lived experiences are not that different from someone with a similar complexion who was born on a different continent. The other 5% of the time, I appreciate “African-American” as a term that does specify a group of people who have been traumatized for generations by American slavery and still feel those systemic effects to this day. When we read about Black communities living in poverty, having limited access to healthcare, or the need for Affirmative Action because of decades of educational inequality, it’s usually referring to African-Americans, and I think it’s important that solutions are specific in their target audience if they’re going to succeed.

Tell us about your experience as a Black academic professional in STEM.

Expectedly, this is also a very complex question, so I’ll try to cover the bases with some examples: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Let’s start with the good. In the late 1960s, admissions departments around the country began considering race as a factor when admitting new students, creating policies aimed to accept more students of color who had historically been excluded from colleges and universities. In the past couple of decades, the awareness of this educational imbalance and its need to be corrected has only grown, with emphasis on active and intentional intervention. Many organizations, including government-funded programs, have pools of money to incentivize Black students to enter STEM fields. Having 10+ years of higher education and being able to say, “I have zero debt and never had to apply for student loans” is truly a beautiful thing. Now the bad… I will preface by saying I have been fortunate in my academic career to have had a predominantly positive experience in STEM. In my undergraduate and graduate education, all at predominantly White institutions, I’ve never experienced an overt act of racism. However, covert racism is extremely prevalent and just as harmful. And unfortunately, it’s usually the result of an inherently racist system. Some brief examples of institutionalized racism to which I (and probably most Black people in STEM) have been exposed: being the only Black person in the room; seeing predominantly Black staff in maintenance and service roles on campus but extremely underrepresented in upper level positions; always being asked to be involved with any type of diversity efforts; being a low-income and first-generation student trying to succeed in a field with zero assistance or support from administration because they “don’t see color” and don’t understand why I might need more help than my White peers; attending conferences and seeing how little attention posters by Black students and post docs receive; and giving my own administration four years to recruit more Black faculty, while seeing them take zero interest or action until the world watched another Black man killed by a police officer. And now the ugly… The pressure of being Black in a field where there are so few people who look like me is physically, psychologically, and emotionally exhausting. Physically, being Black in STEM means that I must code switch on a daily basis, which broadly means shifting one’s speech, demeanor, and appearance in ways that will optimize the comfort of others in exchange for fair treatment, quality service, and employment opportunities. I do not do this to fit into a mostly White and Asian field and culture, or to be accepted, but to survive. Historically speaking, African American Vernacular English is perceived as a language indicating a lack of intelligence. If I spoke or carried myself the way I am most comfortable, I would not be afforded the opportunities that I have. I would not be given the chance to allow my intellect to speak for itself. If I want to succeed, I am forced to leave pieces of myself outside of the Mudd Building every day, because I am only given a pass and accepted in this field if I fit the mold that people in power have shaped. I’m even questioning how much of this bio I should share, because my story might make other people uncomfortable, which I think itself speaks volumes. Psychologically, the limited number of Black people in STEM spaces brings that much more weight on those who are there. If I don’t excel, how long before they take a chance on another Black student? If I fail, am I confirming the doubts they already had about my abilities based on me looking different than every other person they’ve had in their lab? If I ask for help, do I lack resourcefulness and initiative? Knowing that I have to work twice as hard to get half as far as my peers is mental gymnastics, and being an example for my race is a burden that I did not ask for but am yet required to carry. Emotionally, every Black person in STEM is still a Black person in America. That alone carries with it an added stress that I cannot expect others to understand. How do I explain that someone who looks like me was killed by a police officer yesterday (again), and I was too busy crying from that traumatic event that I couldn’t concentrate long enough to study for your exam or sleep last night? When I’m angry about injustices that directly impact me but aren’t of concern to most of my peers, to whom do I go to vent my frustration? That is my experience.

What does Black History Month mean to you?

To me, Black History Month means that Black lives matter. They hold importance and value. They have been, and continue to be, vital to global progress in every sector, despite the degree to which their lives are often devalued and easily forgotten. This month is a period of time set aside for the world to be reminded of the impact that Black people have made towards the advancement of society, which people of all races benefit from to this day. My favorite historical Black figure is Dr. Charles R. Drew, an American surgeon who did research at Columbia’s Presbyterian Hospital and pioneered techniques for blood plasma storage and preservation leading up to World War II. For his work, he was appointed director of the first American Red Cross Blood Bank in 1941. However, just a year later, he resigned from his position, because the U.S. armed forces ruled that blood donated from African Americans had to be stored separately from that of Whites. Dr. Drew is a constant reminder that my little world of scientific research does not get to exist outside of the issues of American society. With every new drug delivery system or therapeutic, it is imperative to consider access and availability thereof for all people, particularly communities most often underserved. We must be citizens as well as scientists and engineers.

What accomplishment(s) are you most proud of, and what do you hope to accomplish in the future?

There are many things of which I am proud and by which I am humbled. I am a 26-year-old Black man who will soon have a Ph.D. in Biomedical Engineering from Columbia University. I have made positive contributions to my educational institutions in the form of student advocacy, most recently in the Columbia University Senate and the Engineering Graduate Student Council. I tutor underserved students in NYC and have personally seen their standardized test scores improve and them matriculate to four-year colleges and universities. In the future, I hope to help reshape the way academia operates such that I am not one in a million, and a child’s future is not derailed simply because of their zip code. I want to help underrepresented minorities who pursue STEM to feel supported enough to stick with their major after freshman year and even pursue advanced degrees. I want to help fix a health system that still sees higher mortality rates and reduced access to care for Black people than White people. I want to have established myself as a respected leader and intellectual such that I have the privilege of being my true self, free of preconceived judgment, whenever I walk through a door.

What advice would you give to others who wish to pursue a degree and/or career in BME?

1) Create a support system. That could be maintaining contact with family, making new friends, seeking out social groups, and anything in between. The road is challenging with the best of help, and near impossible to traverse alone. 2) Explore career paths early. Just because you’re studying BME does not mean that’s the only career you’re qualified for, and just because you get a Ph.D. doesn’t mean your only job option is being a professor. You have options. The sooner you discover which possibilities you might most enjoy, the sooner you can shape your own academic journey and emphasize the things that make you happy.

COLUMBIA BME ACADEMICS

With every new drug delivery system or therapeutic, it is imperative to consider access and availability thereof for all people, particularly communities most often underserved. We must be citizens as well as scientists and engineers.

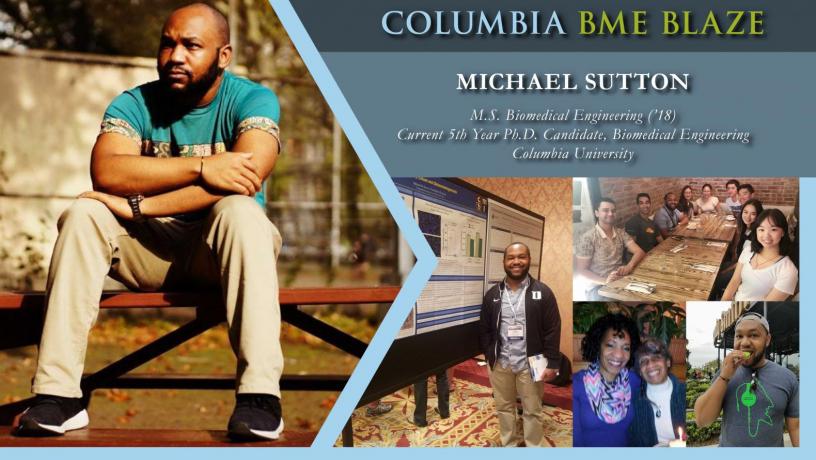

Images (clockwise from left):

1. Morningside Park in Harlem (friend had a cool new camera he wanted to break in).

2. Presenting my poster at the Musculoskeletal Biology Workshop in Sun Valley, ID.

3. Kam Lab lunch at Thai Market.

4. Spring break at Universal Studios.

5. My mom (left) and grandma (right), celebrating my grandma’s 75th birthday.